5 Rare Experiences Only Possible in the Antarctic Interior

Most people picture Antarctica as a coastline: penguin colonies, sculpted icebergs, and Zodiac landings that shift with wind and swell. But the interior is something else entirely. Once you leave the ocean behind, you trade wildlife density for scale, silence, and atmospheric phenomena you can’t really grasp until you’re in it.

This isn’t a “do it in an afternoon” add-on. The Antarctic interior demands precise timing, aviation planning, weather flexibility, and strict environmental procedures. But if you’re drawn to places that feel genuinely out of reach, it’s hard to imagine anything more rare.

Below are five experiences that can only happen deep in the Antarctic interior; plus the practical reality behind each one, so you know what makes them possible.

1) Touch down on a blue-ice runway

A runway made of ice sounds like a travel myth until you feel the wheels bite into it.

In parts of the Antarctic interior, naturally occurring “blue ice” forms when wind and sublimation remove surface snow and expose dense glacial ice. At places like Union Glacier, that hard-packed blue ice can support wheeled aircraft; one reason it’s become a major gateway for deep-field logistics.

What makes it rare isn’t the runway alone. It’s the chain of conditions required to use it safely: visibility, wind, temperature, and a flight plan that accounts for how quickly the continent can change its mind.

If you’re researching operators who specialise in this kind of access, it helps to start with an overview of exclusive Antarctic interior travel from trusted experts, especially the practical realities behind it: who coordinates the aircraft, what the delay plan looks like, and how interior routes are built around safety margins rather than wish lists.

You’ll also want to look for teams that explain their aviation partners, contingency days, and how they handle knock-on effects when a flight slips.

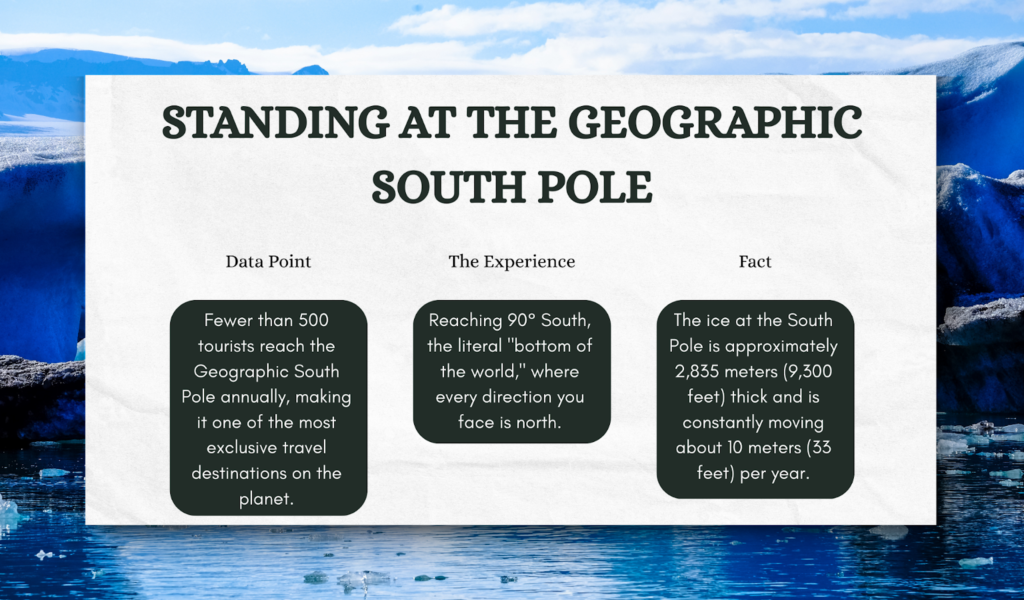

2. Stand at the South Pole and feel your compass become irrelevant

At 90°S, geography does a quiet magic trick: longitude stops mattering, and every direction you face is north.

You’ll usually see two markers: the ceremonial pole (a striped pole topped with a globe and surrounded by flags) and a separate geographic marker that has to be repositioned regularly because the ice sheet moves.

What makes this moment interior-only is simple: there’s no sea route to the Pole. Getting there typically involves flying into the deep field and working within strict operational windows.

The payoff isn’t just the photo. It’s the strange, steady clarity of the place: thin air at high elevation, a horizon that reads like a ruler, and a sense that “arrival” means something different when you’ve reached a mathematical point on a living ice sheet.

3) Watch “diamond dust” turn sunlight into glitter

On the coast, you’re often watching weather move in from the ocean. In the interior, the atmosphere can feel eerily clean; until it sparkles.

Diamond dust is a ground-level cloud of tiny ice crystals that can form in very cold conditions, especially under clear skies. When sunlight hits those crystals, the air can shimmer like it’s full of floating glass.

It’s not guaranteed (nothing in Antarctica is), but it’s far more associated with the kind of cold, dry conditions you find inland. The experience is quiet and surprisingly emotional, because it doesn’t photograph the way it feels. You don’t “see” diamond dust as much as you notice the world has started to glow.

4) Cross a wind-carved landscape of sastrugi

If you’ve ever imagined Antarctica as a flat white sheet, sastrugi will correct you.

Sastrugi are ridges and grooves carved into snow by relentless wind, often forming fields that look like frozen waves. They’re common in wind-exposed polar terrain and can make travel (even short distances) feel physically demanding.

This is one of those interior experiences that’s less “bucket list” and more “body memory.” You feel the texture of the continent in your knees and ankles. You understand why polar travel has always been about endurance, not speed, and why routes and camps are chosen with obsessive care.

If you’re skiing, walking, or moving by vehicle in the interior, sastrugi is part of the reality. It’s also part of the beauty: Antarctica doesn’t just sit there. It’s shaped, daily, by invisible force.

5) Ski (or trek) the “last degree” to the Pole

There’s a reason the phrase “last degree” carries weight in polar circles: it’s the final stretch from roughly 89°S to 90°S; about 60 nautical miles (111 km) across the polar plateau.

This route is widely recognised as a classic South Pole approach because it’s logistically achievable (with the right support) but still demands real effort: hauling a sled, navigating monotony, and earning your arrival step by step.

You don’t do this for comfort. You do it for the rare satisfaction of moving through a landscape so empty it becomes meditative—and for the deep pride of reaching a place that most visitors only ever fly to.

Why the interior feels so different from the coast

Antarctica’s interior is often described as a polar desert. It receives very little precipitation, and the air over the interior can be dry and subsiding, limiting cloud formation.

That dryness and cold create a particular sensory world:

- Sound behaves differently; silence can feel “loud.”

- Light lasts and lasts; shadows stretch in strange ways.

- Small things (a gust, a crystal, a ridge) feel enormous because there’s so little visual clutter.

It’s also why itineraries can’t be rigid.

As Ben Lyons, CEO at EYOS Expeditions, puts it: “On expedition, guests can linger on shore with charismatic penguins, jump into a Zodiac at a moment’s notice when a pod of whales surface nearby, or choose to head ashore later in the day after a morning massage. It’s about having the time and the platform to let the environment dictate the day.”

That idea of letting the environment dictate the day matters even more inland, where weather decisions aren’t just about comfort; they’re about aviation, visibility, and safety margins.

Practical realities you should understand before you chase these experiences

A few factors shape nearly every Antarctic interior trip:

- Short operating season: Most interior logistics happen during the austral summer when light and temperatures are more workable.

- Aviation dependency: Flights are weather-sensitive; delays aren’t a glitch, they’re built into the plan.

- Environmental discipline: Low-impact protocols aren’t optional. Your operator should be able to explain waste systems, fuel handling, and site protection in plain language.

- Conservative decision-making: The best teams don’t “push through”; they wait, reroute, or stop.

Next steps (so you can plan responsibly)

If you’re juggling weather buffers, flight holds, and gear checklists for an Antarctic interior itinerary, an itinerary tracker helps you keep the moving parts visible, especially when plans shift day by day and your “schedule” is really a series of decision windows.

If you’re considering the Antarctic interior, here’s what to ask before you get emotionally attached to a specific map pin:

- What’s the primary access route (and what are the realistic delay scenarios)?

- How many contingency days are built in, and what happens if you lose them?

- What are the medical and evacuation plans in a weather-limited environment?

- Which environmental protocols are used for camps, waste, and aircraft operations?

- What’s the minimum “must-see” experience, so the trip still feels worth it if weather reshapes the itinerary?

Because standards in Antarctica are designed to protect the place (not just your experience), IAATO’s visitor briefings are worth reading before you go; they explain the practical rules that guide real-world operations.